Just had an idea for my first billion-dollar company. Tomorrow, I start building it.

Reflecting on My Failure to Build a Billion-Dollar Company

In 2011, I left my job as the second employee at Pinterest — before I vested any of my stock — to work on what I thought would be my life's work.

I thought Gumroad would become a billion-dollar company, with hundreds of employees. It would IPO, and I would work on it until I died. Something like that.

Needless to say, that didn't happen.

Now, it may look like I am in an enviable position, running a profitable, growing, low-maintenance software business serving adoring customers. But for years, I considered myself a failure. At my lowest point, I had to lay off 75 percent of my company, including many of my best friends. I had failed.

It took me years to realize I was misguided from the outset. I no longer feel shame in the path I took to get to where I am today — but for a long time, I did. This is my journey, from the beginning.

A weekend project turned VC-backed startup

The idea behind Gumroad was simple: Creators and others should be able to sell their products directly to their audiences with quick, simple links. No need for a storefront.

I built Gumroad the weekend I thought up the idea, and launched it early Monday morning on Hacker News. The reaction exceeded my grandest aspirations. Over 52,000 people checked it out on the first day.

Later that year, I left my job as the second employee at Pinterest — before I vested any of my stock — to turn Gumroad into what I thought would become my life's work.

Almost immediately, I raised $1.1M from an all-star cast of angel investors and venture capital firms, including Max Levchin, Chris Sacca, Ron Conway, Naval Ravikant, Collaborative Fund, Accel Partners, and First Round Capital. A few months later, in May 2012, we raised $7M more. Mike Abbott from Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers (KPCB), a top-tier VC firm, led the round.

I was on top of the world. I was just 19, a solo founder, with over $8M in the bank and three employees. The world was starting to take note.

We grew the team. We stayed focused on our product. The monthly numbers started to climb. And then, at some point, they didn't.

To keep the product alive, I laid off 75 percent of my company — including many of my best friends. It really sucked. But I told myself things would be fine: The product would continue to grow and no one far from the company would ever find out.

Then, TechCrunch got wind of the layoffs and published "Layoffs Hit Gumroad As The E-Commerce Startup Restructures." All of a sudden, my failure was public. I spent the week ignoring my support network and answering our customers' concerns, many of whom relied on us to power their businesses. They wanted to know if they should look for alternative products. Some of our favorite, most successful creators left. This hurt, but I don't blame them for trying to minimize the risk in their own businesses.

So what exactly went wrong, and when?

Failing in style

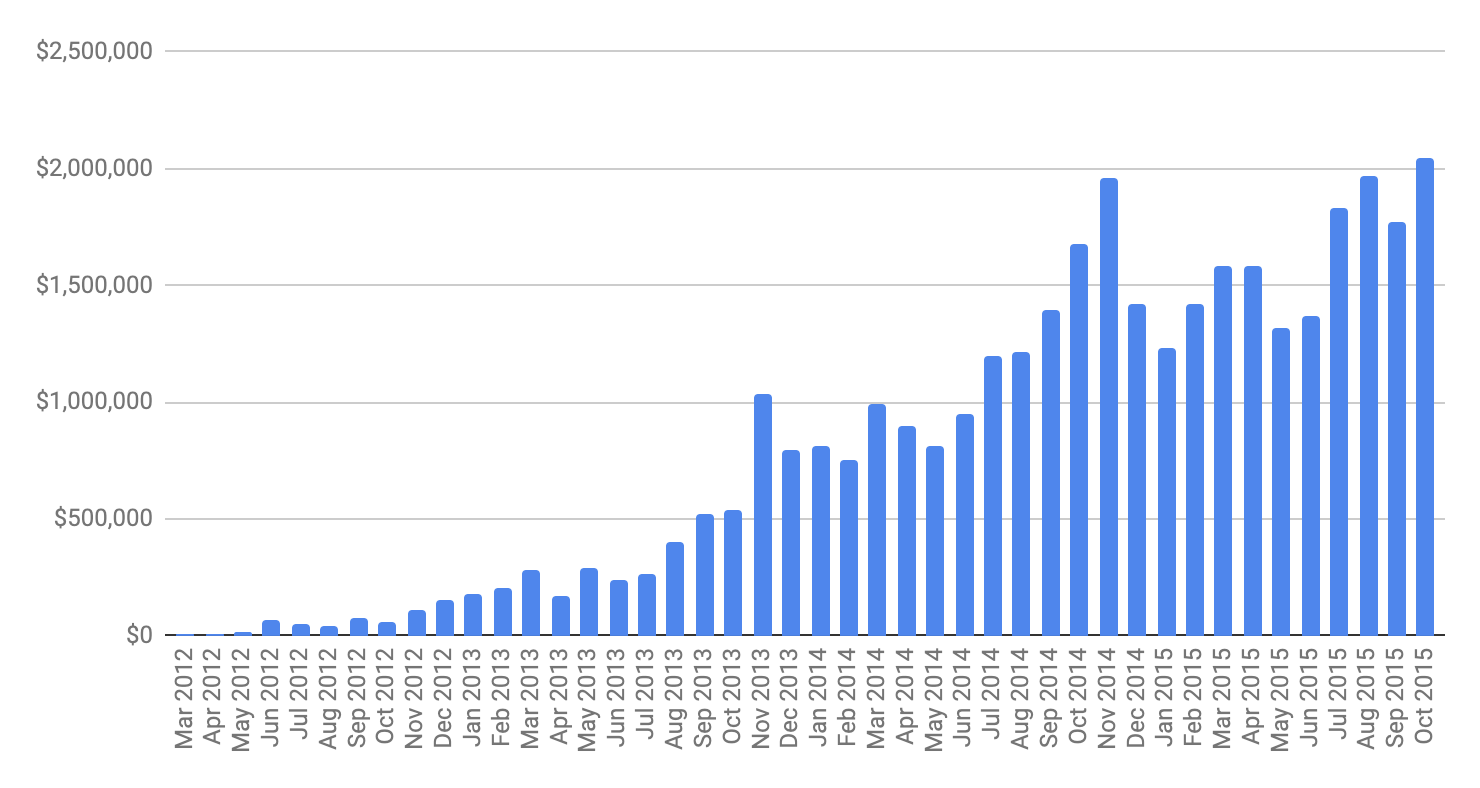

Let's start with the numbers. This is our monthly processed volume, until the layoffs:

It doesn't look too bad, right? It's going in the right direction: up.

But we were venture-funded, which was like playing a game of double-or-nothing. It's euphoric when things are going your way — and suffocating when they're not. And we weren't doubling fast enough to raise the $15M+ Series B (the second major round of funding) we were looking for to grow the team.

For the type of business we were trying to build, every month of less than 20 percent growth should have been a red flag.

But at the time, I thought it was okay. We had money in the bank and product-market fit. We would continue to ship product and things would work out. The online creator movement was still nascent; the slow growth wasn't our fault. It always looked like change was right around the corner.

But now, I realize: It doesn't matter whose "fault" it is; we hit a peak in November 2014 and stalled. A lot of creators absolutely loved us, but there weren't enough of them who needed our specific product offering. Product-market fit is great, but we needed to find a new, larger fit to justify raising more money (and then do it again and again, until acquisition or IPO).

In January 2015, after our final double-or-nothing hail-mary, our bank balance dipped below 18 months of runway. I told my 20-person team the road ahead would be a tough one. We didn't have the numbers to raise a Series B, and we would have to work really hard over the next nine months to get even close. To that end, we deprioritized everything except features that would directly move the needle. Many were not core to our business, but we needed to try everything we could to get our monthly processed volume to where it needed to be.

If we succeeded, we would raise money from a top-tier VC again, hire more people, and pick up the journey where we'd left off. If we didn't, we would have to drastically downsize the company.

In those nine months, when the whole team knew we were fighting for our company's life, not a single person left Gumroad. From "this is gonna be hard," to "yep, turns out it was," every single person worked harder than ever.

We launched a "Small Product Lab" to teach new creators how to grow and sell. We shipped a ton of features, including weekly payouts, payouts to debit cards, payouts to the U.K., Australia, and Canada, various additions to our email features, product recommendations and search, analytics to see how customers are reading/watching/downloading the products they've purchased, and add-to-cart functionality. And that was just between August and November.

Unfortunately, we didn't hit the numbers we needed.

Slim down or shut down?

Looking back, I'm glad we didn't hit those numbers. If we'd doubled down, raised more money, and appeared in the headlines again, there would have been a very real possibility of even more spectacular failure.

With that off the table, our options were:

Shut down the business, return the remaining money to investors, and try something new.

Continue with a slimmed-down version of the company to aim for sustainability.

Position the company for an acquihire.

Some of my investors wanted me to shut down the business. They tried to convince me that my time was worth more than trying to keep a small business like Gumroad afloat, and I should try to build another billion-dollar company armed with all of my learnings — and their money.

I tended to agree with them, to be honest. But I was accountable to our creators, our employees, and our investors — in that order. We helped thousands of creators get paid, every month. About $2,500,000 was going to go into the pockets of creators — for rent checks and mortgages, for student loans and kids' college funds. And it was only growing! Could I really just turn that faucet off?

If I sold the company, it would be mostly for our stellar team — and I would no longer be able to control the destiny of the product. There were too many acquisition stories of companies promising exciting journeys and amazing synergies to come — and ending with a deprecated product a year later.

Selling was certainly tempting. I could say I sold my first company, raise more money, and do this all again with a new idea. But that didn't sit right with me. We were responsible to our creators first. That's what I told every new hire and every investor. I didn't want to become a serial entrepreneur and risk disappointing yet another customer base.

We decided to become profitable at any cost. The next year was not fun: I shrunk the company from twenty employees to five. We struggled to find a new tenant for our $25,000/month office. We focused all of our remaining resources on launching a premium service.

In June 2015, a few months before our layoffs, our financials looked like this:

- Revenue: $89,000 for the month

- Gross profit: $17,000

- Operating expenses: $364,000

- Net profit: -$351,000

A year later, in June 2016, our monthly numbers looked like this:

- Revenue: $176,000 for the month

- Gross profit: $42,000

- Operating expenses: $32,000

- Net profit: +$10,000

It hurt, but it meant creators would keep getting paid. It also meant that we were in control of our own destiny.

From skeleton crew to lifestyle business

It got worse from there.

Gumroad was no longer the venture-funded, fast-growing startup our investors and employees signed up for. As everyone else found other opportunities, the skeleton crew fizzled from five to one.

I was basically alone. I didn't have a team, nor an office. And San Francisco was full of startups raising gobs of money, building amazing teams, and shipping great products. Some of my friends became billionaires. Meanwhile, I was running a "measly" lifestyle business. It wasn't what I wanted to do, but I had to keep the ship from sinking.

Now, I understand some people would dream to be in that position. But at the time, I just felt trapped. I couldn't stop, but there was only so much I could do as an army of one.

I shut off the rest of the world. I didn't tell my mom about the layoffs — she had to read the article and tweets herself to find out. My friends were worried, but I assured them I was neither depressed nor suicidal. I left San Francisco for long stretches at a time, thinking that some travel would give me adequate distance. It only made me more lonely.

Every day, I woke up and took care of all of Gumroad's support queries. I tried to fix all of the bugs I could. Often, I had to ask for help from former Gumroad engineers. They were all employed by then, but they always found time to help. Once all things Gumroad were taken care of, I tried to go to the gym, and if I had the willpower, work on a side project (a fantasy novel). Most days, I failed.

To me, happiness is about an expectation of positive change. Every year before 2016, there was an improvement in my expectations — in the team, the product, or the company. This was the first time in my life when the present year felt worse than the last.

Living in San Francisco was already a struggle. When Trump won the election, I ended up leaving for good.

New beginnings

Then one day, everything changed. Again. I'm wary about sharing this part of the story, because I don't know if there is anything to learn from it. But it happened, so here it is.

On November 27, 2017, I got this email from KPCB, our lead investor:

I am following up our conversation a few months ago. KP would like to sell our ownership back to Gumroad for $1. Can we discuss this week?

Mike had left KPCB to start a new company, and KPCB didn't want the operational headache of appointing a new board member. Plus, it helped their taxes. In one fell swoop, our liquidation preferences (how much we would have to sell for before dollars started going to employees) went from about $16.5M to $2.5M. All of a sudden, there was a light at the end of the tunnel. Small, dim, and far away, but present. There was a path to an independent business, not beholden to the go-big-or-go-home mentality I signed up for when I raised money.

One investor joined them. We've bought back a couple more, since then. I keep the rest of the investors up-to-date with a brief email every few months.

The future came into focus: I could grow a small team, slowly buy back our investors, and build Gumroad into a meaningful business focused on our creators. We would never become a billion-dollar company, and that started to feel okay. Certainly, the thousands of creators selling on Gumroad wouldn't mind.

Finding new forms of impact

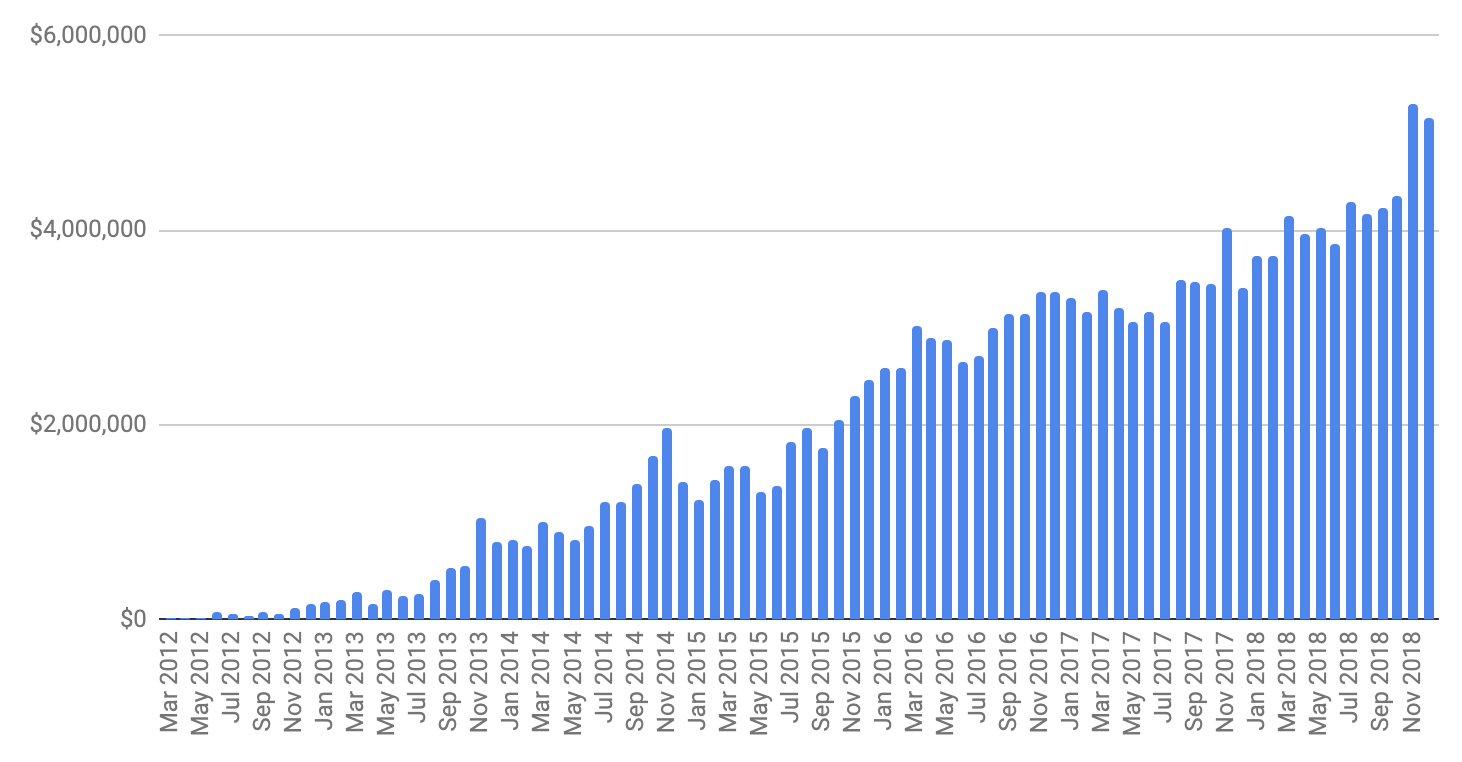

The eight years I worked on Gumroad were full of personal ups and downs. There were months where I worked 16 hours a day, but there were also some months where I worked four hours a week. Here's one way to picture that time:

Can you tell which is which? I can't. We had a sales team for a few years, then we didn't. Can you tell when we made the switch? I can't.

It doesn't matter how amazing your product is, or how fast you ship features. The market you're in will determine most of your growth. For better or worse, Gumroad grew at roughly the same rate almost every month because that's how quickly the market determined we would grow.

Instead of pretending to be some sort of product visionary, trying to build a billion-dollar company, I'm just focused on making Gumroad better and better for our existing creators. Because they are the ones that have kept us alive.

Creating and capturing value

At a CEO Summit many years ago, my all-time hero, Bill Gates, took the stage. Someone asked him how he dealt with failing to capture so much value. Microsoft was huge, sure, but tiny compared to the total impact it has had on the world and on humanity.

Bill's answer: "Sure, but that's true with all companies, right? They create some value and succeed in capturing a very small percentage of it."

I am now more focused on creating value than capturing it. I still want to have as large an impact as possible, but I don't need to create it directly or capture it in the form of revenue and valuation.

Take Austen Allred, for example. He's raised $48M for his startup Lambda School, and he got his start selling a book on Gumroad.

I shifted my focus from selling my book (using Gumroad, the platform he built) to growing a VC-backed company (which he invested in). We still disagree on some things I’m sure, but everyone could learn a lot and quickly by getting out of his or her bubble.

Startups have been founded by former Gumroad employees, and dozens more companies have been massively improved by recruiting our alumni. On top of that, our product ideas, like our credit card form and inline-checkout experience, have proliferated across the web, making it a better place for everyone — including those that have never used Gumroad.

While Gumroad, Inc. may be small, our impact is large. There is, of course, the $178,000,000 we have sent to creators. But then there's the impact of the impact, the opportunities that those creators have taken to create new opportunities for others.

Opening up about our financials

I've found other ways to create value, too. After the layoffs, I didn't talk to anyone about Gumroad. Not even my mom. And after moving away from San Francisco, I felt pretty disconnected from the startup community.

As a way to re-engage with the community, I thought about sharing our financials publicly. Founders starting their own companies could learn from our mistakes, utilizing our data to make better decisions.

It was scary: What if we don't grow every month? It could scare off prospective customers. It's something I would never expect a startup seeking venture capital to do. It makes sense to hold those cards as close to your chest for as long as possible when you must raise money, hire people, and compete for customers with other venture-seeking startups.

But, since we were not any of those things anymore, it was easier to share that information. We were profitable, and a no-growth month won't change that. So in April 2018, I started to release our monthly financials publicly.

Gumroad in April: GMV: $4.2M (down 2%) Revenue: $273K (down 2%) Gross profit: $65K (up 34%) Let me know if you have any questions!

Ironically, more investors have reached out (we're just interested in raising money from our customers for the moment, thanks!), more folks want to contribute to Gumroad, and our shift in focus has brought us closer to our creators.

And instead of freaking out about how "small" Gumroad actually is (like I thought they would), our creators have grown more loyal. It feels like we're all in this together, trying to earn a living doing what we love.

Soon, we're also planning to open-source the whole product, WordPress-style. Anyone will be able to deploy their own version of Gumroad, make the changes they want, and sell the content they want, without us being the middleman.

In 2018, we donated over $23,775 (eight percent of our profits) to different causes. We raised money for the hurricane relief efforts in Puerto Rico and the floods in Kerala. We helped fund the Presence-of-Blackness project in speculative fiction, and a Mexicanx publication.

Seeking the non-binary

For years, my only metric of success was building a billion-dollar company. Now, I realize that was a terrible goal. It's completely arbitrary and doesn't accurately reflect impact.

I'm not making an excuse or pretending that I didn't fail. I'm not pretending that failure feels good. Everyone knows that the failure rate in startups — especially venture-funded ones — is super high, but it still sucks when you don't reach your goals.

I failed, but I also succeeded at many other things. Gumroad turned $10 million of investor capital into $178 million (and counting) for creators. Without a fundraising goal coming up, we're simply focused on building the best product we can for our customers. On top of all that, I'm happy creating value beyond our revenue-generating product (like these words you're reading).

I can't wait until I'm successful so I can write about failure.

I consider myself "successful" now. Not exactly in the way I intended, though I think what I'm doing now counts.

Where did my singular focus on building a billion-dollar company come from in the first place? I think I inherited it from a society that worships wealth. I don't think it's a coincidence that Bill Gates was my all-time hero and the world's richest person. Ever since I can remember, I've equated "success" with net worth. If I heard someone say "that person's really successful," I didn't assume they were improving the well-being of those around them, but that they'd found a way to make a ton of cash.

Wealth can be a measure of being able to improve the well-being of those around you, as seems to be the case for someone like Bill Gates, who has invested heavily in philanthropy. But it's not the only way to measure success, nor is it the best one.

There's nothing wrong with trying to build the next Microsoft. I personally don't think billionaires are evil. And there's a part of me that wishes I was still on that path.

But for better or worse, I'm on this one now.

Gumroad is a product of many people's hard work, including our alumni: Leigh McCulloch, Sidharth Shanker, Anish Bhayani, Kathleen Warner, Heather Whiles, Benjamin Nguyen, Steve Kaye, Tuhin Srivastava, Avinash Ananth, Joel Packer, Katsuya Noguchi, Matan-Paul Shetrit, Amir Haghighat, Ian Atha, Emmiliese von Clemm, Kate Yu, Sri Raghavan, Ryan Delk, Al Hertz, Travis Nichols, Maxwell Elliott, Phil Howes, Ben Reynolds, Michael Klocker, Bryan English, Laura Biester, Jake Heimark, Aaron Relph, Ben Walsh, Greg Terrono, Donald Huang, Paul McKellar, Francisco Gutierrez, Kyle Doherty, and Jessica Jalsevac. Thank you.