"Listen" - a story in three parts.

From Bubble to Bubble

A year ago, I lived in San Francisco. I spent over $2,000 a month for one bedroom in a two-bedroom apartment in the Mission District. Outside of working on my startup, I devoured books on my Kindle and brooded with my fellow liberals about Trump and the GOP on Twitter. Most everyone I knew was agnostic.

I had my whole life planned out. Decades of startups, at least one of which would hit it big. A retirement full of vapid, but pithy tweets.

Today, I live in Provo, the most conservative (and religious) city over 100,000 people in America. I live in a one-bedroom apartment that costs $800 a month. I no longer tweet as much, and especially not about politics. A majority of my friends, including my girlfriend, are religious, and most of them are conservative. I go to church every Sunday.

What changed?

A quarter-life crisis

In 2014, I was the founder of a 20-person VC-backed startup called Gumroad that helps creators of all stripes sell their work.

In 2015, I had to lay off over half of the company. Our growth wasn't reaching the 20%-a-month we needed to raise the funding we required to grow at the same, aggressive pace. I decided to pivot the company towards a sustainable business model. That meant nixing the office and having to let many of my friends go. It was the right decision — we attained profitability, and while we can't ship as quickly, Gumroad will be around for the long haul.

It also meant that Gumroad no longer looked like my magnum opus. While it remains a great business today, I felt like I was stagnating.

So, I dabbled. In my spare time, I started writing a fantasy novel in the vein of The Giver. I began learning how to draw. I invested in my hobbies, though I did not have a long-term project to replace Gumroad. I was used to solving problems, but now I didn't know what problem to solve. Like many others, I was consumed and horrified by the presidential election — was there a problem here that I could work on?

I didn't really know what I wanted to do, but I felt like San Francisco wasn't going to tell me. My days were filled with friends that thought like me, and meetings in which we patted each other on the back. We knew the solutions to the world's problems — the rest of the world just had to catch up.

I wanted to work on something new, and I needed new ideas. So I moved to the place most full of people not like me: Provo, Utah. A writing class taught by one of my favorite authors, Brandon Sanderson, at Brigham Young University served as the final impetus.

I did some research in the week between deciding to move to Provo and my flight. The facts I learned only bolstered my warped view of the sort of people I expected to meet: church-going and God-fearing, very white and not very woke. And ecstatic about Trump.

If you don't know who I am, you might have assumed a whole lot of things about me, too. The clothes I wear. The kinds of food I enjoy. How much I swear. If you did, you would have done what I did when I moved to Provo. What everyone does when they think about anyone, really, except for themselves.

So, what did I expect of America's most conservative bubble, a place where Hillary Clinton garnered just 14% of the vote and less than 1% of the population was black? It sounded like hell to me.

Culture shock (and lack thereof)

I gave away all of my furniture and landed in Provo on a Sunday, five suitcases in tow, hoping for some grand epiphany about my path forward. Three Mormons skipped church to pick me up from the airport. One of them had seen my moving announcement on Facebook and sent me a message.

"Just so you know, we didn't vote for Trump," Brigham said as he drove me around the whitest place I'd ever lived.

"Who did you vote for?"

"We voted for Evan [McMullin]," Brigham said, indicating himself and his friend, David, "and Jesse voted for Hillary. I wish I could have."

"Why?"

"It's Trump, dude."

"I mean, why didn't you vote for Hillary?"

"She's… Hillary. If it were anyone else…"

The conversation was a hint of things to come: it was full of apologies. Mostly about the Mormons that voted for Trump, but there was also genuine admiration for many things about liberal strongholds.

I had assumed that Provo was happy being Provo — white, male, and Mormon-dominated. I hadn't thought to consider that they wanted change just like I did.

They were envious of San Francisco's racial diversity (while I complained about how much further we had to go). They lauded the focus on women in the workforce (while I talked about how sexist the tech industry was). They spoke ill of their reliance on cars and the negative effects on the environment, while I spoke ill of San Francisco's public transportation.

It turned out, life in Provo is not too dissimilar from life in San Francisco. Why would it be? I found myself an apartment, signed up for the neighborhood gym, and located my default coffee shop. I worked on my novel, drew, and had meals with anyone that was willing.

Learning the language

I knew I wasn't experiencing a representative data sample of Provo's voter demographics — these people were mostly under forty and worked in the tech industry or were at least familiar with it — but almost everyone I talked to identified as conservative.

I learned that we had similar views on a lot of stuff. We wanted the same problems solved. We both wanted to minimize climate change, lower inequality, and decrease healthcare costs.

"Must have been hard, being a Republican in San Francisco."

What? I'd clarify that I voted for Hillary, not Evan McMullin, Gary Johnson, nor Trump.

"But you're a conservative?"

Not really, no. I volunteered for Bernie Sanders in the primary. I think the Democratic platform is better at solving the problems I care about solving.

If this was a conversation with an internet stranger, the conversation would have ended somewhere around here. Thankfully, it was in person and over pizza.

As mentioned, I identified as progressive and they identified as conservative. While we agreed on so much, the language we used made it seem like we did not. It was as if we had access to totally different dictionaries.

This is most pronounced when talking about social issues, such as racism.

Racism, to them, meant that I was saying that they couldn't help but believe that Black people are inferior to White people. That racism was part of their soul and identity, and that it was explicit and intentional. Of course, when I called a stranger on the internet racist, I didn't mean any of that.

To me, racist means that you advocate for laws that uphold a system of racial discrimination. For example, if you oppose the legalization of marijuana, you are racist.

When I used those words, I meant that they were passively supporting a system that empowered White people over Black people. And that they continue to support a racist system built on a foundation only possible by genocide of native peoples.

Yes, and so do I. We're part of the same broken system: the America of today. And if I, a self-righteous liberal, decide to vote for Hillary Clinton and do basically nothing else, am I any better than them?

Wasted time

Because I have made a lot of progress in Provo and have learned these things about conservatives, I look back at the time I spent in San Francisco and see a lot of wasted time.

I think it was unavoidable, but I spent too much time thinking and talking about Trump and persecuting conservatives. There are enough tweets out there covering anything I'll want to say anyways. I am happier now to channel my energy into thy neighbor, and focus on the impact of specific policies versus the idiocracy.

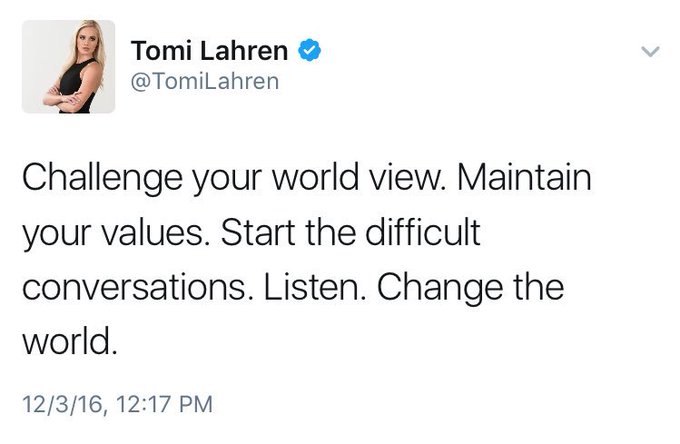

I look back and see the hundreds, if not thousands, of things I tweeted. They were funny, maybe, but besides inflate my ego and follower count, I'm not sure what impact they had.

Today, I only debate in person. Anything else is pointless, because it is too easy to walk away. I make sure we're pulling from the same dictionary, and I make sure we're aligned on the same goal, and not about making sure the other person converts to their side. (Warning: This does not work with Mormon missionaries.)

Room for improvement

I have learned plenty from Provo. But here are some things I still hope to teach it:

Provo should care more about their own outgroup, the areligious. In Provo, Mormons rule. If you're a non-Mormon, you're in the minority regardless of your skin color. Your lifestyle is infringed upon and your vote is disenfranchised. Public transport is closed on Sundays, as well as the municipal gym. It would be more welcoming to people like me if Sundays didn't feel so hostile.

Mormons are scared of the outside world, and I wish they weren't. It is not uncommon, at Church or otherwise, to hear that the world is getting worse (as Christian doctrine states that it must before the Second Coming). This is a belief the vast majority of conservatives hold.

The truth is there: Christianity is eroding. Every generation is more agnostic than the last. The music and movies we are exposed to contain more nudity. It's easier than ever to get access to porn or drugs. Gay marriage is legal, and more genders are being recognized. The list grows.

But I believe the world is the best it's ever been, and I bring it up whenever I can. Extreme poverty is shrinking; the polio vaccine has all but eradicated the disease; fewer kids are dying in the first five years of their life; more humans live under a liberal democracy than ever before. This list also grows.

I understand that their priorities are not mine. I do not share their enemy (it's Satan). But I can take the time to educate them about my worldview, and many of them have come around to it, just like I have to theirs.

Finally, I wish Mormons consumed more art. Reading books and watching movies and listening to music is a great way to reach outside of one's bubble and experience a perspective entirely different from their own. Movies like Get Out and Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, and albums like DAMN. speak to important truths far outside the Mormon bubble but get little traction inside of it. This realization has also got me re-amped about the work we're doing at Gumroad to empower the creative class.

The bubble that keeps on bursting

Provo hasn't changed much in the year that I have been here. San Francisco hasn't either. But I have. My bubble has, at least a little bit, burst (and reformed, and burst and reformed again).

I visited San Francisco last Christmas, and I tried advocating for conservative politics at bars. There is a stigma that certain ideas aren't taken seriously in San Francisco anymore. I didn't see that. Just like conservatives embraced me and my ideas, liberals gave me the same grace.

I now believe that both sides are composed of mostly open-minded people that aren't represented in the NYTimes nor on Fox News nor in the latest viral political Tweet. They're at home and at school and at work trying to make ends meet. They don't care about that level of exposure. They are working privately to solve those problems. Maybe you're one of them! If so, hi!

When I moved to Provo, I didn't expect to walk in anyone's shoes. I was affluent, young, agnostic, and had the freedom in my life to pivot my entire life because I felt like it. I was not, and could not pretend to be even close to the median American voter. But I am a little closer.

Realizing that even the most liberal of governments cannot fix climate change alone, I have reduced my consumption of red meat. I have deleted Twitter and Reddit off of my phone, and seek to have more in-person conversations. I invest more time in my creative hobbies and volunteer for causes that I support. I see the value of a Christ-like figure in one's life, and support that journey in those around me. And I am reignited about the impact that Gumroad and our creators can have upon the world, sharing their perspectives through their products.

I am not a fundamentally different person than the one I was a year ago, but I am a little bit better.